by Kathryn Holleman

When Ned Anderson talks to people about becoming organ donors, he knows exactly what he’s asking of them. He’s lived it.

On the most difficult day of their lives, Ned and his wife, Diana, donated their only child’s tissue and liver after he died in a car wreck.

But Ned also knows what donation means to the person receiving the organ. He’s lived that, too. Five years ago, Diana’s life and that of a critically ill baby were saved by the donation of a single liver.

Knowing both sides of donation makes him that much more passionate about it. “I am going to beat the drums every day, raising awareness,” he says.

“What are we doing today?”

Ned, 74, and Diana, 71, grew up in Mountain Home, Arkansas, met as teenagers and married after Diana graduated from high school.

After joining the Army, learning to fly and earning an engineering degree, Ned embarked on a full and varied career. He started a trucking business that hauled jet engines for Fed Ex. He traveled the world and built coal mines and casinos. He invented electronic devices, including a check reader for Walmart. And a battle with lymphoma inspired him to invent an electronic record-keeping system and vein finder.

And through it all, Diana was by his side, waking up every morning to ask, “What are we doing today?”

With the birth of their son, life was even more fulfilling.

A hero and an angel

From the time of her marriage, Diana prayed for a child. Chad was the answer to her prayers. A happy, bright child, he participated in the family’s adventures and grew into a handsome, active young man.

One night, Ned and Diana got a phone call. A tractor trailer had hit Chad’s car as he and his fiancée drove home from meeting with the minister who was to perform their wedding. The Andersons raced to the Memphis trauma center where the couple had been taken. When they arrived, doctors told them Chad was brain dead. He was only 30.

When Ned was in the military, he and Diana had signed up as organ donors. Chad had joined them as soon as he was old enough to understand. So, in their grief, Ned and Diana made what they call an easy decision. They asked to donate Chad’s usable organs and tissue.

Knowing their son donated tissues that saved or helped more than 100 people comforted the Andersons, says Ned. “We felt like he’s a hero for what he was able to do,” he says.

Diana says that as people of faith, she and Ned feel Chad watching over them. “He’s our angel,” she says.

Too sick to transplant

For the next dozen years, the Andersons filled their lives working, volunteering and raising awareness for organ donation. Then, Diana got sick. With stomach pains, increasing weakness and shortness of breath, Diana — once ready-for-anything — could barely get out of bed.

Testing revealed she had non-alcohol-related cirrhosis (scarring) and liver failure. She had also developed hepatopulmonary syndrome — her liver caused her lungs to malfunction. A liver transplant was her only hope to survive.

Ever the data-conscious engineer, Ned researched and found the Washington University/Barnes-Jewish Hospital liver transplant team’s outcomes were among the best in the U.S. So, the Andersons came to BJH.

At first, the news was discouraging. Diana’s age and condition made her a risky transplant candidate. But the physicians, nurse coordinators and other members of the WU/BJH liver transplant team tackled her issues one by one, until she was finally added to the liver transplant waiting list. At that time, she had only weeks to live.

One liver, two recipients

On June 14, 2014, the Andersons received another call at their Arkansas home: A suitable donor liver had become available.

The donor liver matched not only Diana, but also a critically ill baby in the St. Louis Children’s Hospital intensive care unit.

Luckily, the WU/BJH liver transplant team is one of the most experienced transplant teams in the U.S. at performing “split liver” transplants — where one donor liver is divided between two recipients, typically an adult and child — with the adult receiving the larger liver portion and the child receiving the smaller. Both liver sections regenerate into a full-size organ in about six weeks.

The Andersons and the child’s parents agreed to the split liver procedure. Though they had utter confidence in the liver transplant team, the Andersons prepared for the worst, saying their good-byes to each other. And again, Diana leaned on her faith. “I wasn’t afraid,” she says. “I knew if I didn’t make it, I’d be with Chad sooner.”

Both transplant operations were successful, and Diana initially moved out of the ICU the day after surgery. But her partial liver wasn’t yet able to filter enough toxins out of her blood to reverse the hepatopulmonary syndrome. She needed a ventilator to help her breathe and moved back into the ICU, in a coma.

For the next several weeks, the liver transplant team and the critical care staff worked and waited as Diana struggled to recover.

Slowly, her condition improved. Finally, by late July, she was awake and breathing on her own, with her transplanted liver healthy and grown back to full size. On July 25, Diana was discharged from BJH to The Rehabilitation Institute of St. Louis for about a week before returning home.

Five years later, with Diana restored to health and taking only one tablet a day to keep her body from rejecting her new liver, the Andersons are back to “grabbing all we can out of life.” Much of that involves giving to others and their community and, of course, talking about the need for organ donors every chance they get.

Ned explains donation and transplant by asking whomever he’s talking to to imagine themselves or their loved ones needing a transplant. For instance, he’ll ask a mother to imagine her child needs a donor organ. Would they refuse a donor organ to save their child? If not, how could they possibly refuse to sign up for the chance to save someone else’s child? He convinces most of the people he talks to.

But then Ned and Diana know that putting yourself in the position of someone who can donate or who needs an organ can change your perspective. They’ve lived it.

A gift of coal and friendship

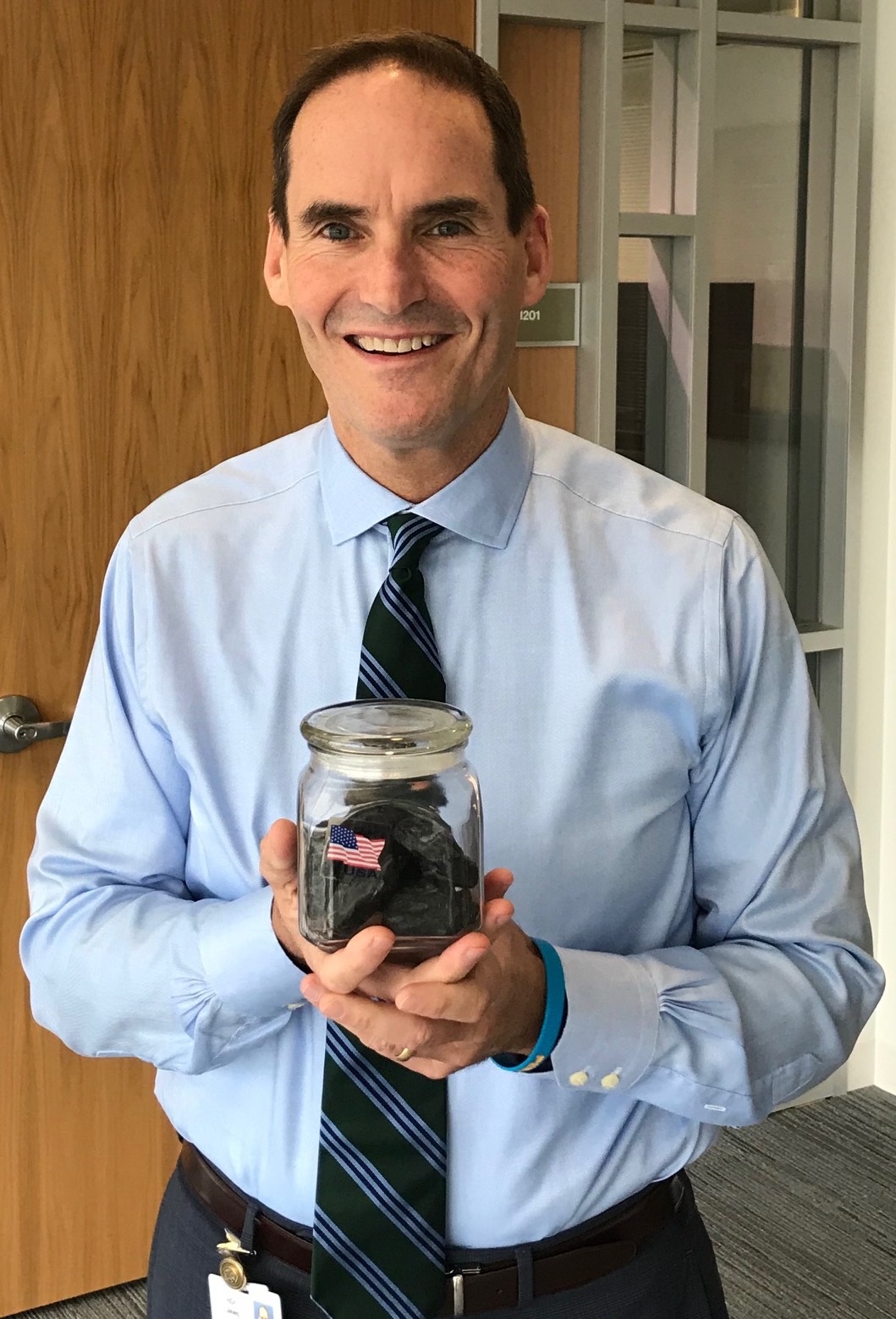

BJC president and CEO Rich Liekweg has a jar of coal in his office, given to him by Ned Anderson. Though he’s joked that it’s the coal he should have gotten in his Christmas stocking as a child, it’s actually a symbol of the friendship that started in an elevator at Barnes-Jewish Hospital.

BJC president and CEO Rich Liekweg has a jar of coal in his office, given to him by Ned Anderson. Though he’s joked that it’s the coal he should have gotten in his Christmas stocking as a child, it’s actually a symbol of the friendship that started in an elevator at Barnes-Jewish Hospital.

As Diana Anderson lay comatose after her 2014 liver transplant, her husband, Ned, seldom left the intensive care unit. But one day, at her nurses’ urging, he took a break to go to the BJH cafeteria. In the elevator on the way, he encountered Liekweg, who was then the hospital president.

Liekweg greeted Ned and asked if everything was going well.

“No, it’s not,” said Ned.

Liekweg listened quietly as Ned poured out the story of how Diana — his wife of close to 50 years — was struggling to survive.

“Is there anything I can do?” Liekweg asked when Ned was done.

“Say a prayer for us,” said Ned.

“I will do that,” Liekweg replied.

Several weeks later, Ned again ran into Liekweg.

“You’re back?” Liekweg asked.

“We’re still here,” Ned told him. But he also told Liekweg the prayer he had promised to say must have been pretty good — Diana was awake and doing well.

Ned took Liekweg back to Diana’s room to introduce him.

“He comes into the room and I have no makeup on and a feeding tube,” laughs Diana. “He says he’s so glad to meet me. I thought, what a fine man he is to take the time to come meet me.”

The meeting was the start of a friendship that endures today.

The Andersons say they were immediately struck by Liekweg’s humility and genuine interest in their well-being.

Liekweg says, “Ned and Diana are a 21st century love story. I feel so blessed to have met them, and I count them as my dear friends who have embraced me, BJC, WUSM and even my family. They have experienced the impact of organ transplantation from every possible angle and now have their own personal mission to share their story in the hopes of inspiring others to help save a life … and to celebrate those who gave their life to save others. We were destined to meet each other that evening, in that elevator, at that precise moment, when Ned needed someone to talk to. Lucky for me, I was the only other person on that elevator.”

As much as the Andersons feel that the Washington University/Barnes-Jewish Hospital liver transplant team and critical care staff have become like family to them, Ned says they feel a special kinship with Liekweg. The Andersons stay in touch with emails and in person when they return to St. Louis for Diana’s follow-up care.

Ned had saved 10 jars of coal from a mine he worked on in Alabama to give as remembrances or souvenirs through the years. He finally had one left and he wondered who to give it to. When he met Liekweg, he knew. The jar still sits in Liekweg’s 12th floor office in the Center for Outpatient Health.